The following was written by Brian.

Mintage or Survival Rates? What's More Important?

One of the first questions collectors ask me about a coin they are considering is "what is the mintage?". Of course, if I do not have the answer off the top of my head, I'll look it up. However, the research doesn't and shouldn't end there. One of the oft overlooked aspects of coin availability is survival rate.

Survival rate is an estimate of the number of coins believed to exist for any particular issue. One good example of a coin with misleading availability is the 1932 Saint Gauden's Double Eagle. The coin had a mintage of 1,101,750. It shouldn't be too difficult to get your hands on one of those, yes? Well, no, as that particular issue was ordered melted by the US Government. In fact, most 1932 double eagles were melted following the abandonment of the gold standard in the 1933 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As some of those coins eventually came out of the woodworks, what came to be was a coin with a high mintage, yet an incredibly low survival rate. Estimates are somewhere around 175 mint state graded coins and literally zero known in circulated grades.

Another good example is the 1876-CC 20 Cent piece. Coin mintage was 10,000, which is by all standards low, but the survivability of around 16 known is shockingly low. In a letter dated March 19, 1877, the Director of the Mint (Henry R. Linderman) ordered the Superintendent of the Carson City Mint (James Crawford) to melt down all Twenty Cents still on hand at the time. Presumably, many, if not most of the 1876-CC Twenty Cents were included in the melt. An estimated 16-20 1876-CC Twenty Cents are known today.

So word to the wise; be sure to check survival rate before considering a coin too expensive when it shows a high mintage. There could be more to the story.

The following was written by Brian.

I often overhear the question 'how is a PL/DMPL coin created'. I have heard everything from die polish to early die state and everything in between as reasons, but the truth is that it is the complete die preparation (not just simple polishing) that creates these eye appealing and in-demand coins.

The creation of DMPL and PL Morgan Dollars mostly occurs in the production process of the individual dies that are used to strike the coins. Dies were made individually from a so-called master hub with all of the major design elements which are then transferred to the individual dies. These dies are then basined, which is where the prooflike factor comes in. During this process the dies were placed against a zinc receptacle that contained water and fine grind particles that were slowly revolving, continually polishing the die. Depending on the amount of time the die was polished a prooflike or even deep-mirror prooflike die could be produced. Q. David Bowers proposes in his Guide Book of Morgan Silver Dollars that the dies that struck DMPL coins were inadvertently polished for too long, but this is merely a theory that has not been confirmed. It is possible that some dies were polished longer than others on purpose, perhaps to show off the quality and workmanship of the employees at the various mints.

As you can see in the images below from PCGS (www.pcgs.com/news/a-look-at-pcgs-designations), the mirrors can be highly reflective and when the devices are frosty enough, it gives the appearance of cameo contrast and in my opinion warrants a premium.

The following was written by Chris.

We deal a fair amount in Swiss Shooting Medals. I love the unique and often ornate designs of them. In fact, I have several in my personal collection. While finally getting around to going through a small lot of them that we bought several years ago, I came across this medal.

I could not find a listing of it in the Richter catalog. Granted, it's not actually a shooting medal. Thanks to my quite rusty skills in the German language that I acquired back in college (well, that and Google translate), I determined that the medal commemorates the inauguration in 1939 of the Swiss Shooting Museum. The legend on the medal is in both German and French.

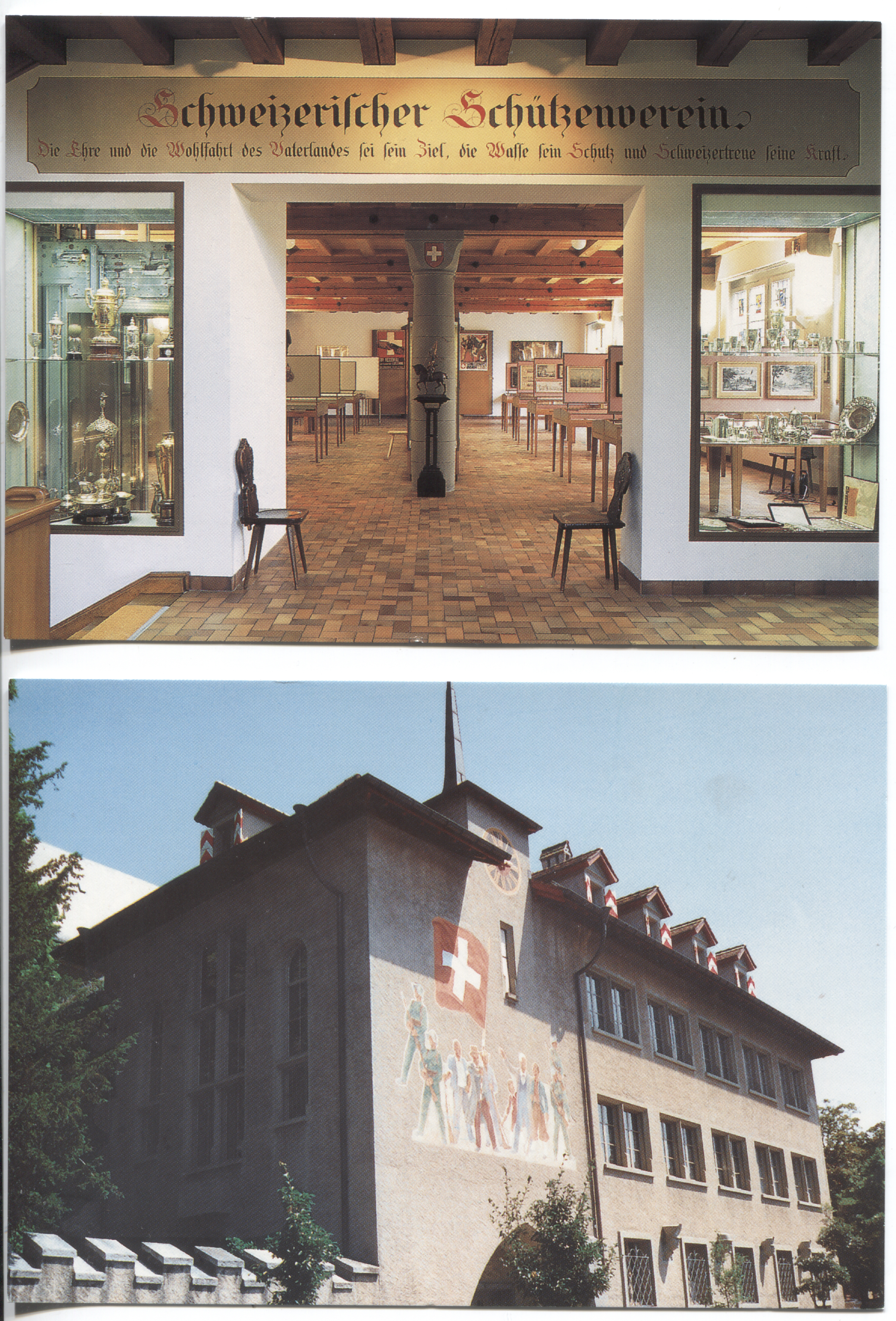

Some further research brought me to this website. This museum is located in Bern, and as you can see it is indeed the one depicted on the medal. I plan on contacting the museum to see if they have seen many of these inauguration medals. If not, I think it would make for an interesting donation for their display.

For further information on Swiss Shooting Medals, head on over to Shootingmedals.com. If you'd like to view our current selection of Shooting Medals, you'll find them in the medals section of our inventory.

Update 7/3/2019:

I reached out to the museum to see if they were familiar with the medal. They of course were and had an example on display and another in their archives. I asked if they would be interested in having a third for their collection and they were delighted. The director of the museum, Regula Berger, sent us a very nice note along with several post cards from their museum.

Chris, I'm with you with regard to Swiss Shooting Medals, especially certain of the Beautiful Women set.

The following appeared in a recent E-Sylum article:

Jeff Burke submitted this article on his quest to choose and locate a great Saint-Gaudens $20 gold piece for his collection. Thanks. -Editor

“My Quest to Select One Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle Type Coin”

by Jeff Burke

Introduction

Learning more about Saint-Gaudens double eagles has sparked the bibliophile in me! My ongoing fascination with Saint-Gaudens double eagles (SGDE) started with reading books about the 1933 double eagle. I had the privilege of seeing the 1933 Farouk double eagle specimen at the New-York Historical Society in August 2013 (see my “Star of the Show: A 1933 Double Eagle,” in The Nebraska Numismatic Association Journal, vol. 57, issue 4 (October/November/December 2013), pp. 16-19, for more details).

Curious to learn more about these fabled coins, I read Selling America’s Rarest Coin: The 1933 Double Eagle, David Alexander, 2002; Illegal Tender: Gold, Greed and the Mystery of the Lost 1933 Double Eagle, David Tripp, 2004; Double Eagle: The Epic Story of the World’s Most Valuable Coin, Alison Frankel, 2006; and Striking Change: The Great Artistic Collaboration of Theodore Roosevelt and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Michael F. Moran, 2007. I also devoured A Handbook of 20th-Century United States Gold Coins: 1907-1933, David W. Akers, 2008; A Guidebook of Double Eagle Gold Coins, Q. David Bowers, 2004; Renaissance of American Coinage: 1905-1908, Roger Burdette, 2006; and Collecting and Investing Strategies for United States Gold Coins, Jeff Ambio, 2008.

Possessing a large disk of Saint-Gaudens gold has always been visually appealing to me. I previously had a 1922-S PCGS MS 63 double eagle and a 1910-D NGC MS 64 double eagle in my collection. I traded these double eagles for other coins and hadn’t owned a Saint-Gaudens $20 since 2015. To my surprise, I really missed owning one! Perhaps owning a gold coin makes me feel special. I also love the design.

Conducting Research

After contemplating the possibilities, I decided to pursue a better date SGDE in a higher grade. My focus narrowed to an examination of 1923-D double eagles: “A choice or gem specimen is usually a treat to behold, the very definition of eye appeal!” (David Bowers, in reference to the 1923-D double eagle, A Guidebook of Double Eagle Gold Coins, p. 266). I discovered that 1923- D double eagles are plentiful, but have a much smaller population compared to common date SGDE. Here is another reason why I chose this particular coin: “...As most examples (1923-D) are boldly struck and show radiant luster, this date (and mintmark) is often chosen to represent the type if just a single coin is desired.” (Jeff Garrett, Description & Analysis for the 1923-D Saint-Gaudens double eagle, NGC Coin Explorer).

The next step was to order and read Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles: As Illustrated by the Phillip H. Morse and Steven Duckor Collections, by Roger Burdette, ed. by James L. Halperin and Mark Van Winkle, published by Heritage Auctions in 2018. Despite not having a table of contents or index for quick reference, it was a joy to read! My favorite portions were “Background” about United States International Gold Shipment and the engaging Chapter Six - “Lost and Found - Survival of U.S. Gold Coins.” It took Burdette five years to research this masterpiece and another year to write it. (See Wayne Homren’s review of this volume in The E-Sylum, vol. 21, Number 28, July 15, 2018, for more information). This tome is well worth the money!

I learned “...it is estimated that out of 70,290,930 Saint-Gaudens double eagles manufactured between 1907 and 1933, only 2,966,565 coins, or four percent, survive in all states of preservation.” (Burdette, Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles, p. 612). The 1923-D is the last mint marked coin in the Saint-Gaudens $20 series readily available to collectors before surviving populations dwindle and prices escalate. (Burdette, p. 397). The 1923-D saw extensive shipment overseas. “Most pieces seemed to have been preserved in foreign holdings, most likely in Argentina or Brazil (accepted as legal tender), where it was common practice to leave U.S. gold untouched in its original bags.” (Burdette, p. 397).

Making the Purchase  I worked through my old 2007 list of 31 favorite coin dealer websites and other numismatic websites to examine 45 to 50 specimens of 1923-D double eagles. After perusing numerous dealer websites on the Certified Coin Exchange, e-bay and other sites, I kept returning to a 1923-D NGC MS 65* Star Designation double eagle that I saw on the Northeast Numismatics online inventory. Unfamiliar with the NGC Star notation, I conducted some research. According to the NGC Census as of March 21, a total of 1,389 SGDE are listed with the Star Designation, which is 0.14% of SGDE graded by NGC.

I worked through my old 2007 list of 31 favorite coin dealer websites and other numismatic websites to examine 45 to 50 specimens of 1923-D double eagles. After perusing numerous dealer websites on the Certified Coin Exchange, e-bay and other sites, I kept returning to a 1923-D NGC MS 65* Star Designation double eagle that I saw on the Northeast Numismatics online inventory. Unfamiliar with the NGC Star notation, I conducted some research. According to the NGC Census as of March 21, a total of 1,389 SGDE are listed with the Star Designation, which is 0.14% of SGDE graded by NGC.

Tom Caldwell founded Northeast Numismatics in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1964. “Tom is a firm believer that an educated collector is necessary to a strong and sustainable coin market, and has taken great efforts to teach youngsters (and elders) the essentials of coin collecting.” (Northeastcoin.com). Providing numismatic education can help collectors learn more about their collecting interests and encourage others to explore the wonders of our hobby.

I am thrilled to own this beautiful coin! Did it spend decades in Brazil or Argentina? I wanted to keep this 1923-D double eagle next to me forever so I could admire it at my leisure. Reluctantly, I put it in a bank safe deposit box for safekeeping.

Note: Chris Clements of Northeast Numismatics kindly provided obverse and reverse images of my double eagle to accompany this article. Thanks also to Paul Sandler for fielding my questions about Saint-Gaudens double eagle NGC Star Designation coins.

Talk about buying (and reading) the book before the coin! Congratulations on your well-thought-out purchase. Great coin! -Editor

Beautiful coin and great story of how you arrived at this specimen.

Well worthy of the Star designation.

The following was written by Tom:

It’s hard to feel any more patriotic than today, which is Patriots' Day here in Massachusetts. Right here in Concord Center is not too far away from where it all started in 1775 with the “shot heard round the world,” which was the start of the American Revolution. From our office window we have a birds-eye view of the annual celebratory parade. Minuteman groups along with marching bands, scout groups and more make their way along the parade route while thousands of visitors who have come from near and far, watch and celebrate the spectacle.

Speaking of history, the Caldwell family has a long history of involvement in the festivities. Back in the 1960’s I used to march in the parade as a Boy Scout. As the Bicentennial approached, my parents joined the local Minuteman group and also marched in the Concord parade. Later, my two children marched while they were involved in the Scouts.

About halfway through the parade route is the Old North Bridge, at which you’ll find Daniel Chester French’s Minuteman statue. This statue is memorialized on the Concord-Lexington Silver Commemorative Half Dollar (see below). The parade makes a ceremonial stop for speeches as well as a crowd favorite - the reenactment of the famous battle between the British and Colonists at the bridge.

Back in the day as a kid, never would I have thought Concord would become home to my family as well as Northeast Numismatics. Happy Patriots' Day!

I enjoyed your piece, Tom.

Excellent! Glad you enjoyed it.