The following was posted by Marne, our coin photographer.

As Northeast's resident coin photographer I spend some of my time standing at the imaging station at my desk. However, I spend far more hours seated at my computer station processing and uploading images as well as handling all of our web orders.

My past photography work at a portrait studio involved mostly standing, some kneeling, and even crouching or laying on the ground to get that perfect shot. Transitioning from that job to my current job of sitting most of the day has not been easy on my back and shoulders. I've even had to go to some physical therapy sessions.

After Tom switched to a stand-up desk for his office, I looked into the possible benefits of switching to one myself. There are hundreds of articles and studies available to confirm that remaining seated at a desk all day can cause chronic lower back pain and exacerbate circulatory issues in the legs. Hunching to use a mouse and keyboard for many hours can give you upper back, shoulder, and neck pain.

I put off making any changes for quite a while, but then I started feeling uncomfortable on daily basis. Tom and Chris were very much behind the idea of me switching to a workstation that would make me comfortable and keep me healthy! I finally decided to switch to a multi-level workstation that would allow me to both image coins and use my computer at comfortable heights. I knew I could not immediately go from sitting all day to standing all day (I have no idea how Tom could), so I also was given a nice office stool to give my feet and legs a break until I am used to standing for longer periods. Right now I'm sitting about half the day and standing and moving the other half.

So far I must say I really love my shiny new desk and workstation. I even had room to bring in a happy little plant terrarium! As you can see in the images provided, I'm a bit more organized and fastidious about my work area than some. (See our blog post from December 22nd of 2015.) I would highly recommend anyone to try out this type of workstation if possible. Why not prevent discomfort or possible health issues before they even start?

In 1787, Ephraim Brasher, a goldsmith and silversmith, submitted a petition to the State of New York to mint copper coins. The petition was denied when New York decided not to get into the business of minting copper coinage. Brasher was already quite highly regarded for his skills, and his hallmark (which he not only stamped on his own coins but also on other coinage sent to him for assay [proofing]) was highly significant in early America. Brasher struck various coppers, in addition to a small quantity of gold coins, over the next few years.

One of the surviving gold coins, weighing 26.6 grams and composed of .917 (22-carat) gold, was sold at public auction for $625,000 in March 1981.

We recently purchased a 1783-95 Regulated $2 Gold Ephraim Brasher EB Counterstamp

Struck in the final weeks of December and released in January of the new year, the 1916 Standing Liberty Quarter has one of the lowest mintages of any 20th century coin issued for actual circulation with 52,000 pieces. While they are not of the rarity that the date is often purported to possess, the 1916 is a key date in a popularly collected series and no set of Standing Liberty Quarters may be considered complete without an example.

Hermon MacNeil’s design features the Goddess of Liberty standing within a portal or gateway. Her left arm presents a shield and her gaze is fixed to the east, some would theorize toward a war torn Europe. Her right hand holds an olive branch emblematic of America’s desire for peace. With the influence of the “Art Nouveau” style and her right breast showing, much has been made of the partial nudity exhibited in this obverse. The design was changed part-way thru 1917 with Liberty now clothed in chain mail armor.

Number 43 in Garrett’s 100 Greatest U.S. Coins.

Featured below is a CAC approved AU58.

The Half-Union (also known as Judd-1546 and Judd-1548) is a United States coin minted as a pattern, with a face value of fifty U.S. Dollars. It is often thought of as one of the most significant and well-known patterns in the history of the U.S. Mint. The basic design slightly modified the similar $20 "Liberty Head" Double Eagle, which was designed by James B. Longacre and minted from 1849-1907. It is also #19 on the 100 US Greatest Coins Fourth Edition. The two gold pieces are unique and reside in the Smithsonian Institution.

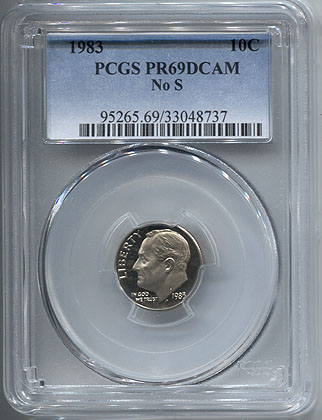

For several different years, some proof Roosevelt Dimes from the San Francisco Mint were struck without the “S” mintmark. For each occurrence, the “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dimes are rare. In a few situations, the coins are significant rarities with only a handful known to exist.

The 1968 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dime was the first situation. Responsibility for making proof dies rested with the Philadelphia Mint and production took place at the San Francisco Mint. At least one die was sent from Philadelphia lacking the “S” mint mark. A small number of dimes were struck with the die and released before the mistake was discovered. Approximately 12-14 examples are known in all grades. One of these, graded by PCGS as PR68 Cameo, sold for an astonishing $48,865 in September 2006.

Two years later in 1970, more proof Roosevelt Dimes were struck without a mint mark. This time production from an entire die pair was released before discovery, resulting in an approximate mintage of 2,200 of the 1970 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dimes.

The 1975 “No S” Proof Roosevelt Dime emerged as the rarest of this error type. An extremely small number of proof coins missing the mint mark were released. The coins were so rare that they were not discovered until 1978 when two examples surfaced. These coins are now considered one of the major rarities of the 20th century with an estimated 2 to 5 pieces known. No examples have been graded by either PCGS or NGC.

One more time in 1983, proof dimes were minted without the “S” mint mark and released in some proof sets. The mintage is estimated at the life of a proof die, which at the time was 3,000 to 3,500 coins.

Psssst…we've got one if you’re interested…