The following was posted by Chris.

Oxford's English Dictionary defines beautiful as pleasing the senses or mind aethestically. As the definition implies, beauty is quite subjective. Everyone's laminated list (if this Friends reference is lost on you, think "hall pass") will be different.

Most coin collectors out there, with a lot of effort and mind-changing, can probably compile a list of their top five most beautiful coins. I decided to put together a list of some of the coins that I consider the most beautiful in the world. Choosing just five was too challenging for me and would have made for a short post. The coins listed here are in no particular order. At the end, you'll find everyone's favorite here at NEN. By the way, if you have a favorite that you'd care to share, please do! We'd be happy to post it.

All images from PCGS CoinFacts.

The 1907 High Relief. Certainly one that will be on many collectors' lists. (I cheated and used an Ultra High Relief image.)

The 1847 Great Britain Gothic Crown. Definitely a top five for me.

The 1839 Great Britain Una and the Lion 5 Pound. Another top five for yours truly.

Central American Republic 8 Reales.

1916-1917 Type One Standing Liberty Quarters.

1935 Connecticut Silver Commemorative. Okay, I'm not a huge fan of the reverse, but I love the oak tree motif.

Libertas American Medal. Got me, it's not a coin, but this famous issue deserves entry. I might have to put this in my top five also.

Draped Bust Heraldic Eagle Dollar. This one is a proof.

1894 German New Guinea Bird of Paradise issues.

France Hercules Silver Francs issues.

1921 High Relief Peace Dollar. (I cheated again, using a satin proof image for this one.)

2017-W $100 American Liberty High Relief. Generally speaking, modern coin designs don't appeal to me. But I figured I'd include something "new" in the list. I think it's the Mint's best modern production.

Now for everyone else's favorites!

1776 Continental Dollar. Tom picked this one.

1915-S Pan-Pac $50 Gold Octagonal Commem. This is Marne's choice.

Mexico 50 Gold Pesos. Steven likes the design of the these.

Deeply mirrored Morgan Dollars. This is Mike's selection.

1836 Pattern Dollar. This popular Cap and Rays design is one of Frank's favorites.

Susan B. Anthony Dollars. Last but not least, Brian is a big fan of this issue.

1943-1974 Mexico 20 centavos in red is a beautiful coin, lots going on, pyramid, cactus, cap and rays, etc

Thanks for sharing, JCoop. We agree!

Identify what this is, where it's from, and approximately when it was made. Send your guess to info@northeastcoin.com. The first correct entry received will win a surprise coin, which will be revealed when we post the answer.

Congratulations to Panda, who correctly determined what this is! It's a 1/4 Baht from Thailand from the mid-1800's. It's commonly referred to as bullet money. Panda's prize is a silver 1 Baht pictured below.

The following was written by Frank.

Capped Bust Quarters have been a favorite of mine for a number of years because they have tremendous value and rarity compared to their larger counterparts (Capped Bust Halves). Only 5,496,984 Capped Bust Quarters were minted from 1815-1838, while 91,088,096 Capped Bust Halves were minted from 1807-1839. It’s also a rather short series; it is quite attainable to put together a date set of business strike coins, with exception to the 1823. Capped Bust Quarters remain relatively affordable in moderately circulated grades. You can easily locate a so-called “common date” XF piece for $500.

The story of how the Capped Bust Quarter came to be is an interesting one. The Mint hadn’t produced any quarters since 1807, which was the last year of the Draped Bust design. The United States began producing Capped Bust coinage with the Half Dollar in 1807. In the early days of the Mint, anyone could bring their silver and gold to the Mint and have them turn your metal into freshly minted coins. The Coinage Act of 1792 states, “That it shall be lawful for any person or persons to bring to the said mint gold and silver bullion, in order to their being coined.” So, if you were in Philadelphia during the early days of the mint, all those gold implants you have could be extracted and made into freshly struck uncirculated quarter eagles, if you were in dire need of some extra cash. The Mint would charge one half percent of the weight of gold or silver to cover their expenses.

Photo courtesy of PCGS

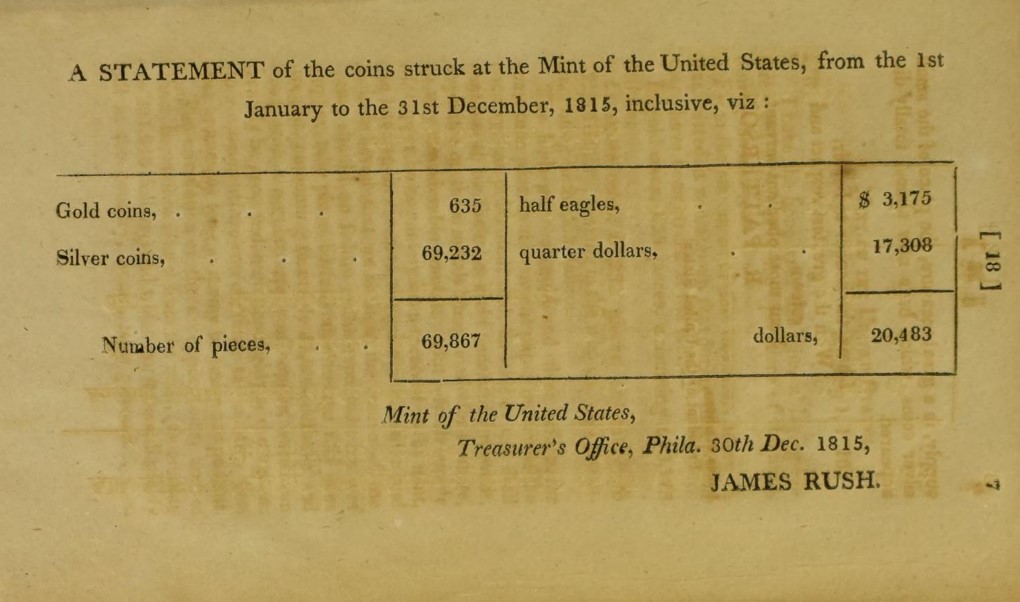

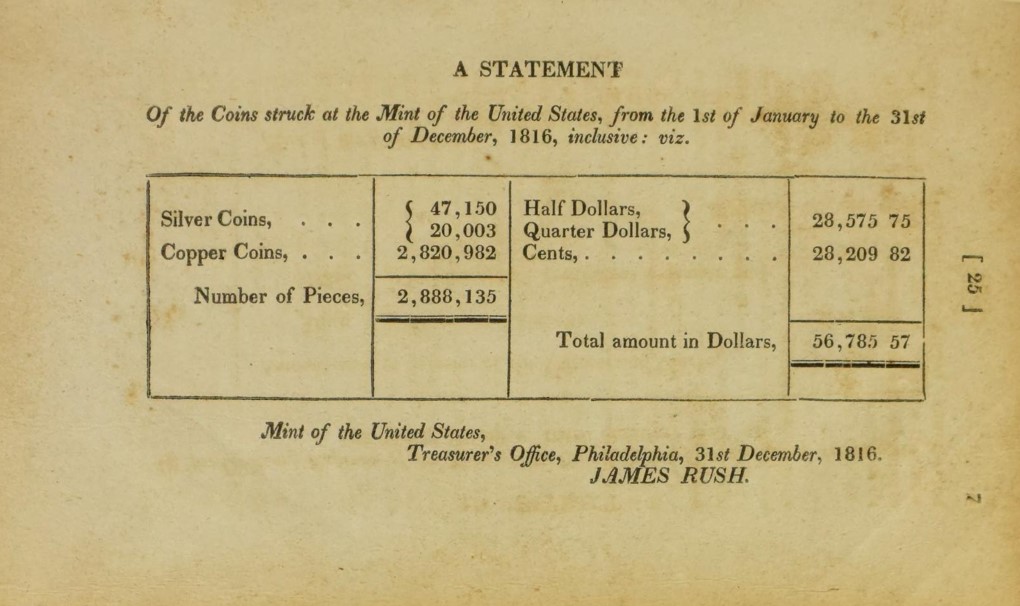

Banks too would often deposit their sums of silver and gold to the Mint and get coins in return. In 1815, the Planters Bank in New Orleans placed a large order of Quarter Dollars from the mint. Bailly Blanchard, the head cashier at Planters Bank, wanted Quarter Dollars because of a local shortage of their Mexican counterparts, the 2 Real (1 Real was equal to 12 ½ cents). You have to remember that Mexican coins circulated alongside U.S. coins up until 1857. The Director of the Mint, Robert L. Patterson, didn’t want to follow through with the order of Quarters because the Mint didn’t have any Quarter Dollar dies prepared. Eventually, Patterson caved and instructed Chief Engraver John Reich to create dies for 1815 Quarters. The total mintage for 1815 Quarter Dollars is 89,235. 69,232 Quarters were struck in 1815 and another 20,003 coins made in 1816 bearing the 1815 date.

Photo Courtesy of Newman Numismatic Portal

Photo Courtesy of Newman Numismatic Portal

Planters Bank would get their shipment of almost 57,500 pieces in December of 1815, the remainder of the coins were paid to the Bank of Philadelphia on December 30th, and Jones, Firth & Co. on January 10, 1816. The large diameter Capped Bust Quarter would be produced until 1828, when it was replaced with the small sized Capped Bust Quarter in 1831, these would be produced until 1838.

Works Cited:

1815 25C (Regular Strike) Capped Bust Quarter - PCGS Coinfacts. https://www.pcgs.com/coinfacts/coin/1815-25c/5321.

1815 – The Year Without New Cents.” Numismatic News, Numismatic News, 2 Apr. 2012. https://www.numismaticnews.net/archive/1815-the-year-without-new-cents.

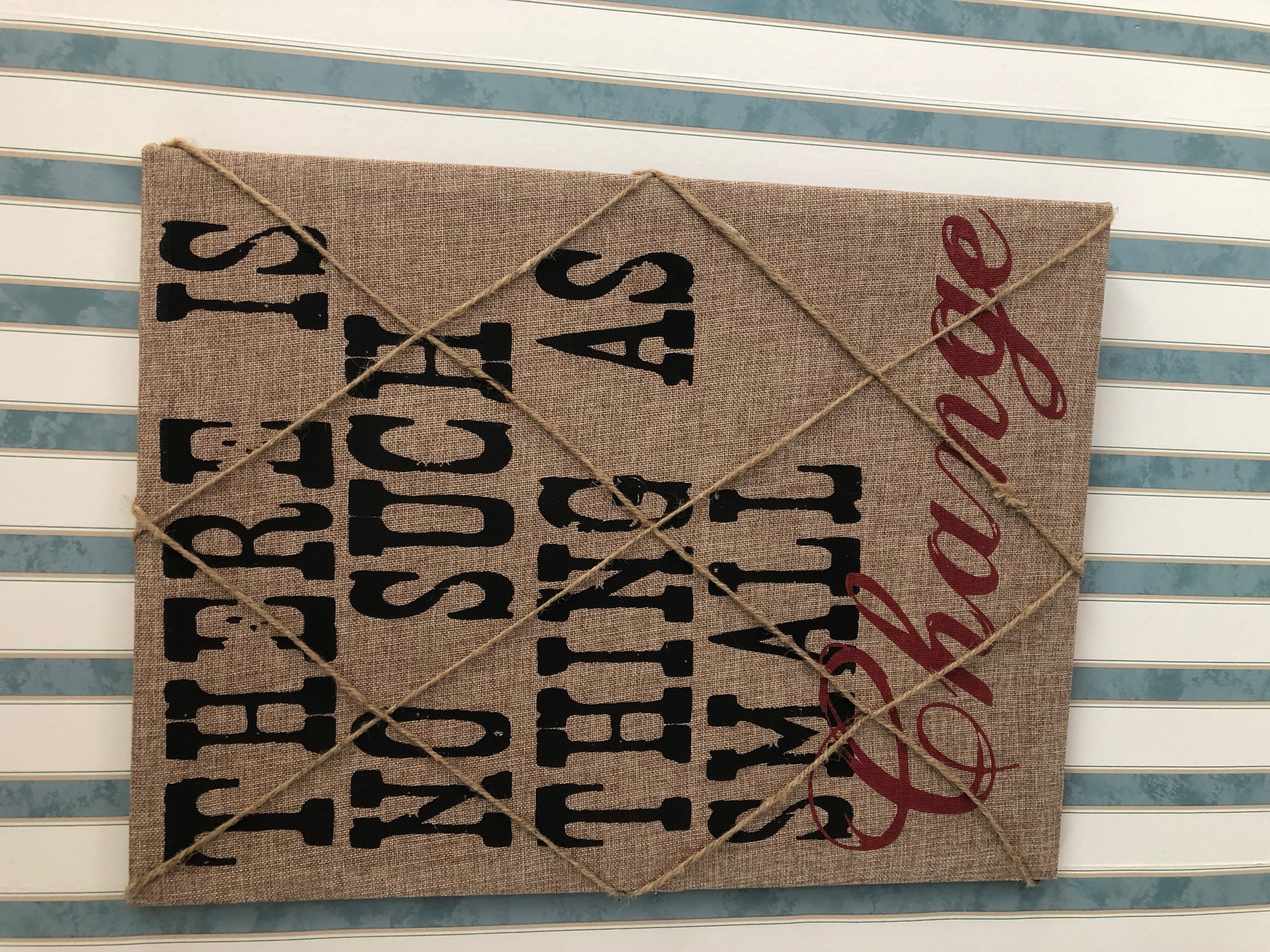

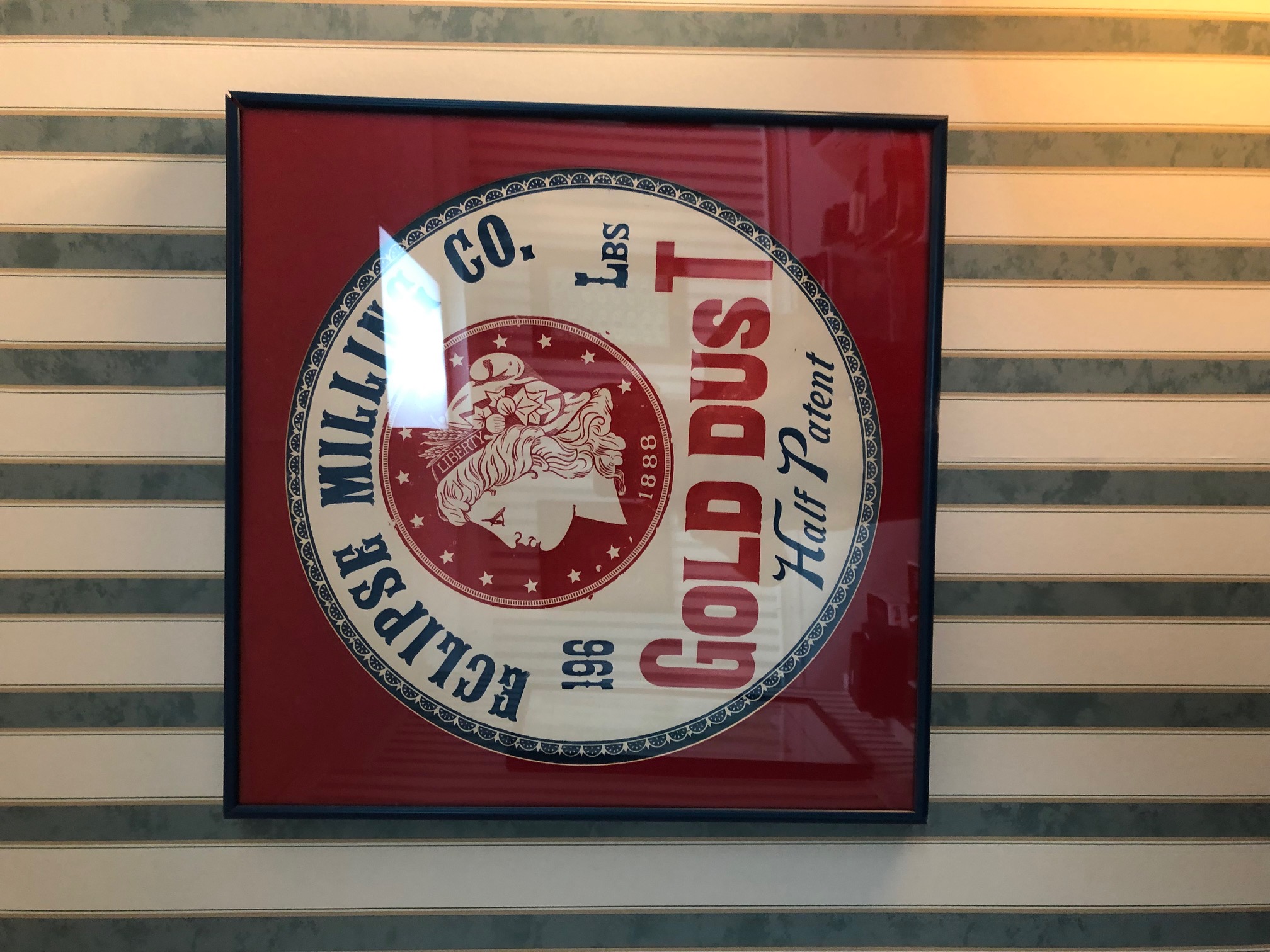

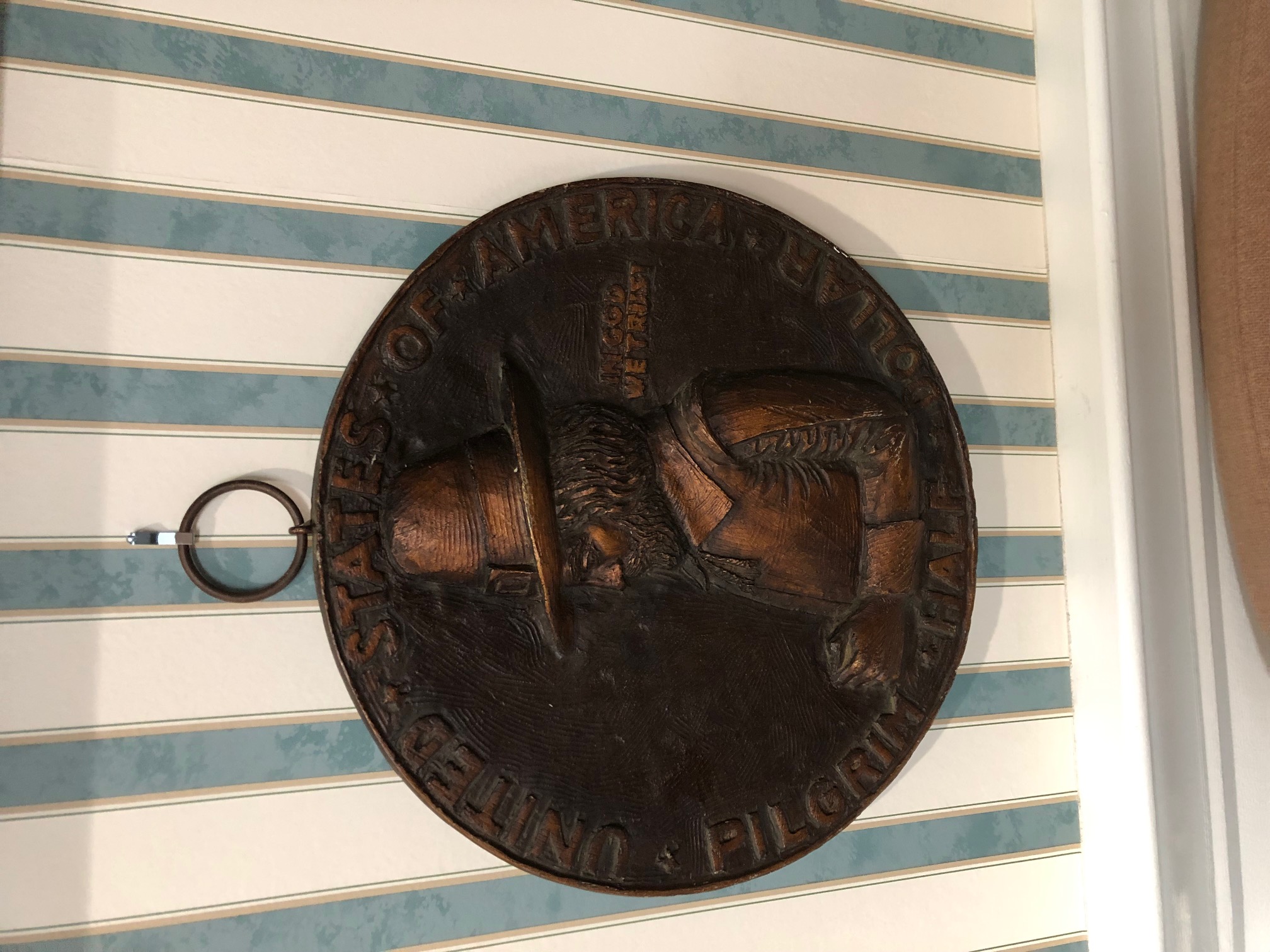

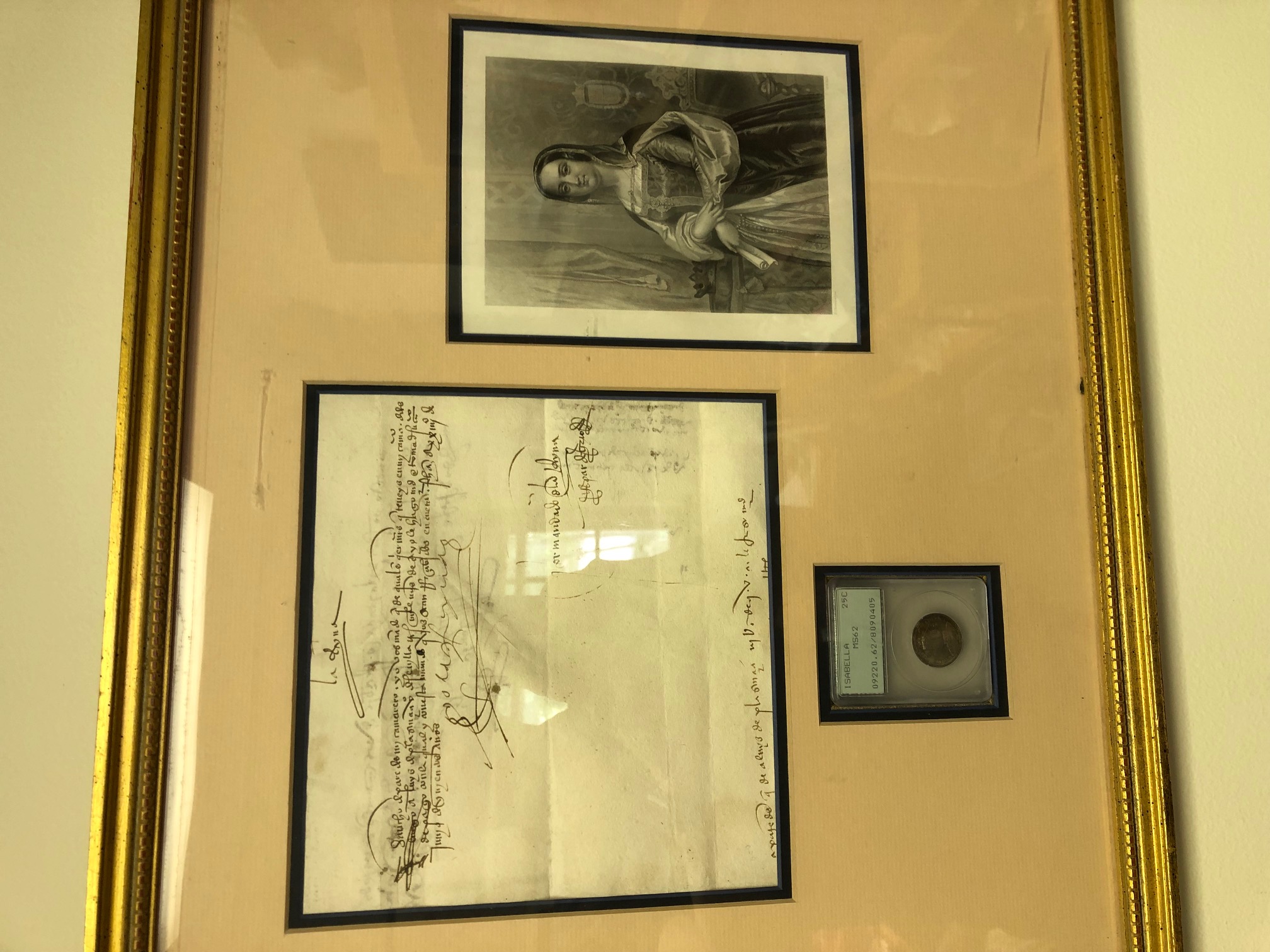

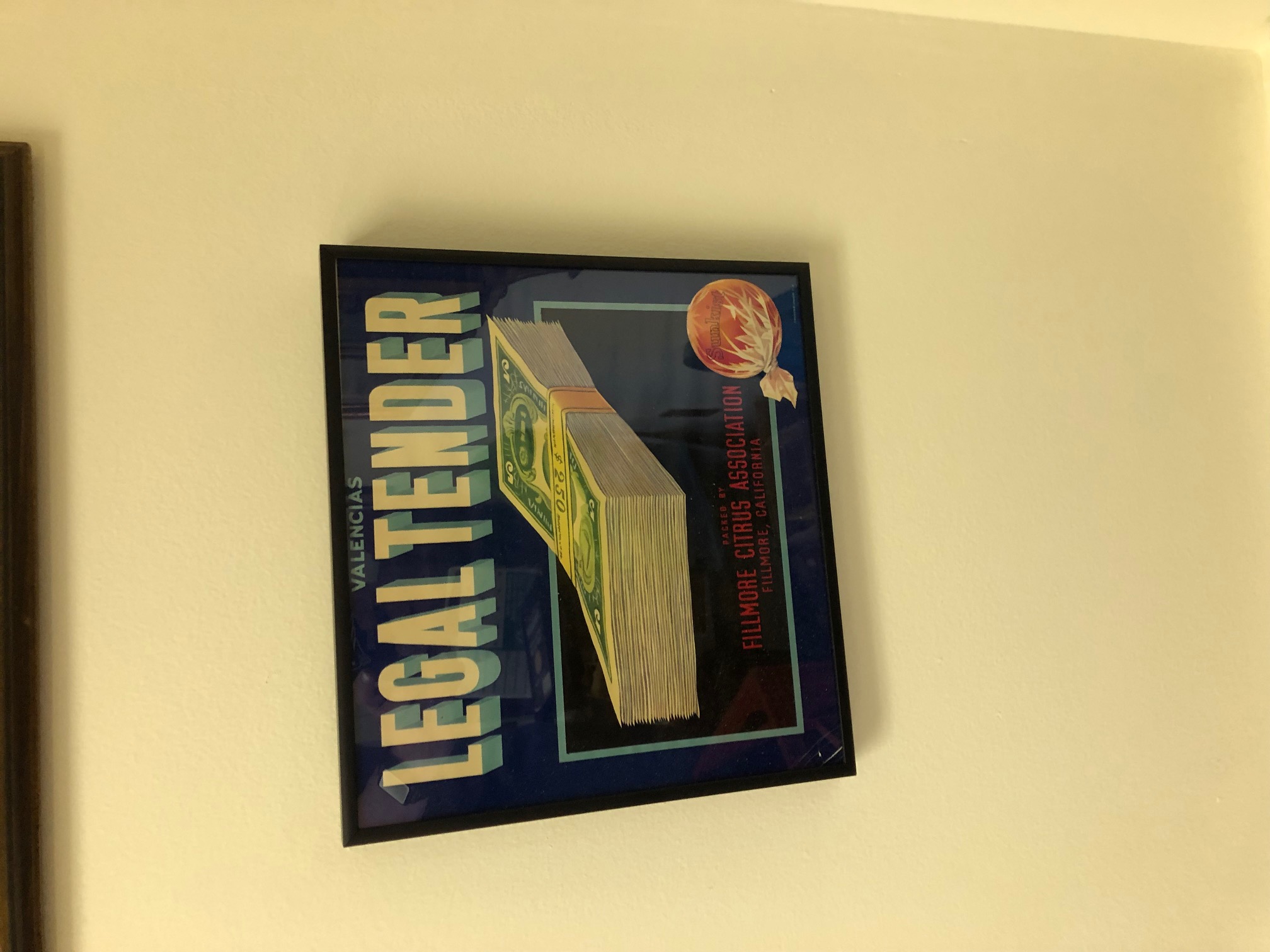

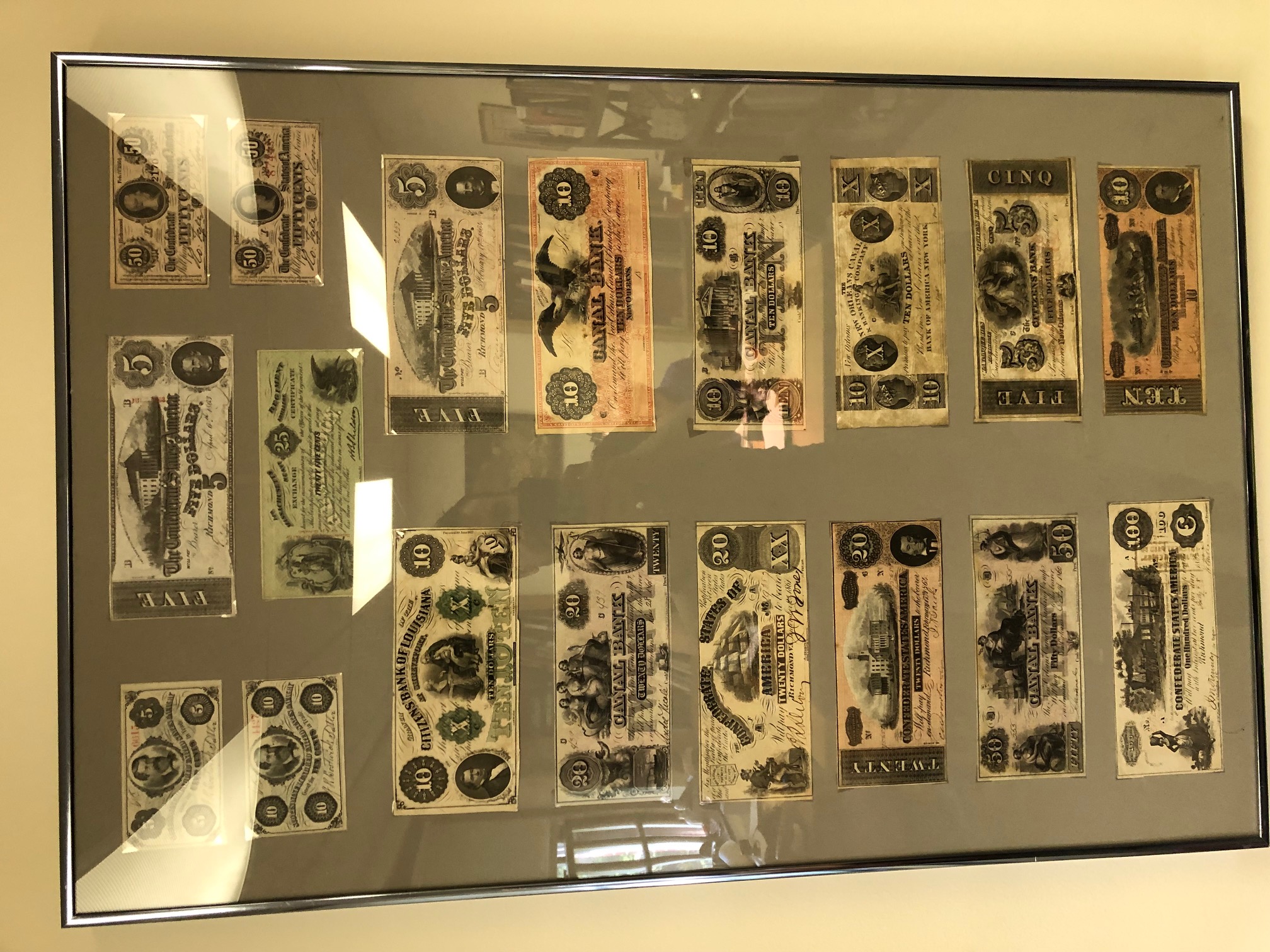

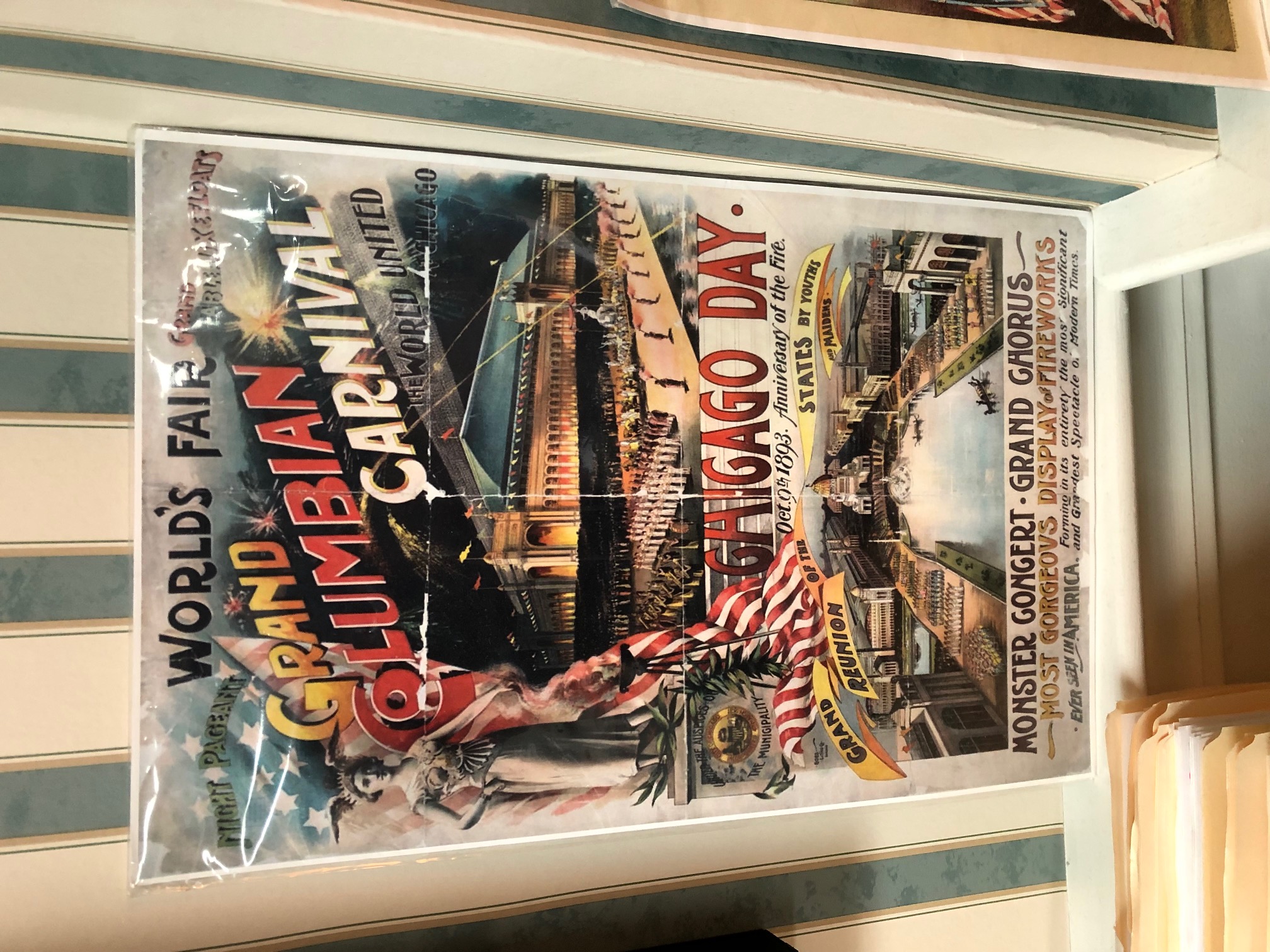

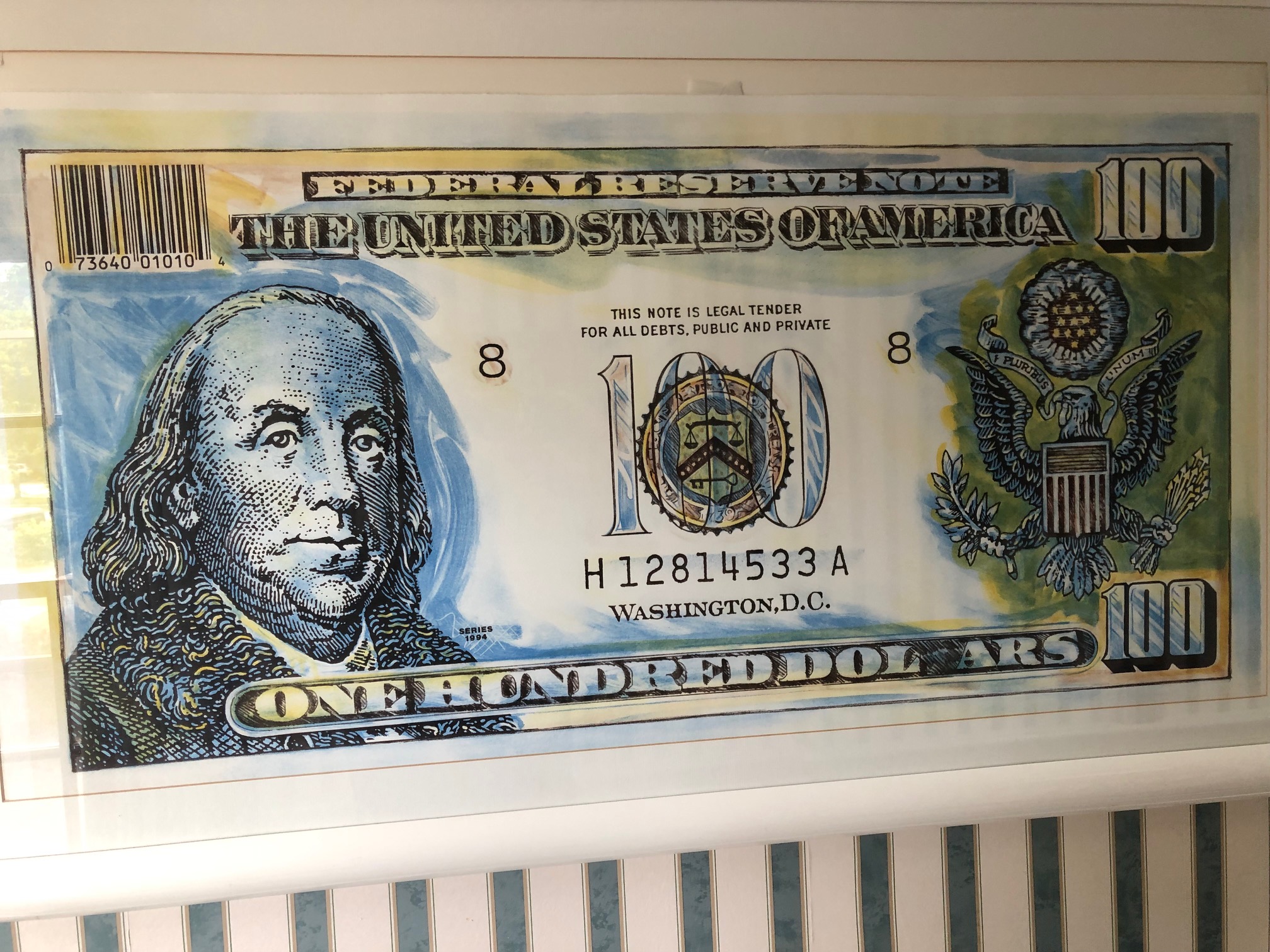

We have quite a bit of numismatically related art hanging in our office. We thought we'd take the opportunity to share some of it. Do you have any hanging or on display in your house that you'd care to share?

(Next post, our personal knicknacks.)

The following was written by Chris.

We attended the Long Beach Coin Expo last week. It occurs to me that I’ve now traveled to this show for a quarter of a century, three times a year. That means I’ve spent well more than a half a year in Long Beach, or nearly 2% of my life, even though I’ve never lived there. Huh. (If you think that’s impressive/depressing, our boss Tom has spent close to two years of his life in Long Beach, never having lived there either.)

Brian, who handles the vast majority of our wholesale sales at coin shows, was out for the count with a back injury. Tom’s son Russell, who has worked many shows in the past for us, traveled in his place. We flew into LAX from Boston early in the week. Personally, I think LAX is a mess. Slow baggage claim, and a ridiculous trek via an overcrowded and/or delayed bus (or take a long walk) to the Uber/taxi lot. I really miss the non-stop flights from Boston to Long Beach. Boarding and deplaning outside on the tarmac via ramps and steps? Supercool old school!

Dealer setup for this show these days starts at noon on Wednesdays. We always attend some pre-show trading that morning (and often the day before). Our trading room at this show was maybe only 25% full, but we were certainly busy the whole time trying to buy and sell.

As mentioned, the show opens at noon for dealers. But not this time. For the first time in my coin show career, dealers were held out in the lobby for close to 30 minutes after the posted start time before being let in. I’m a bit surprised an email wasn’t sent out by the show coordinators after the fact explaining the issue and issuing an apology. We have no clue what the hold up was.

Admittedly, expectations for me were not particularly high for this show. Some wholesale-only dealers with whom I often do lots of business were not in attendance. While formerly one of the major shows of the year, I feel the LB show has slipped down in the ranks a bit. My initial perception of the bourse floor was that it was two-thirds coin dealers, and the rest sports card dealers. Nothing wrong with that whatsoever, as it’s a convention for many types of collectibles. But it’s typically been a coin show with some other business going on.

Once we were in the show for setup, I was able to look through several boxes of wholesale inventory, mostly at my table. I bought what I could, but I passed on so many coins based primarily on price. The market remains solid in most areas that we buy. Has it tempered a bit since its take-off in Spring, 2021? Yes. But prices aren’t falling. Unfortunately the overly aggressive pricing I saw limited my buying. Tom had more success acquiring fresh inventory thanks to his efforts prior to the show. Combined we managed to come home with about six double row boxes of newps.

If anyone cares to hear about our dining experiences, read on. To start, the show provides free beer for dealers later in the day at setup. I choked down my typical amount of light beer (about a 1/3 of the bottle). I’m just not a beer drinker. What I did notice for the first time was a full bar that was set up near the entrance. I did not partake, but I think it was an interesting idea.

Lunch every day was from California Pizza Kitchen. That’s a staple for most of the dealers that choose not to eat an $18 hot dog from the concession stand, as CPK is right across the street from the convention center. Dinner Wednesday night was with a friend of mine from back in my NOLA days. He decided to swing by the show for a day, and it was nice to catch up. We ate at the Auld Dubliner, which is an Irish pub also right across from the convention center. Always great food. And the final night was dinner with Russell at a new and huge Mexican restaurant called Solita. It was decent, but nothing to write home about (yet here I am writing about it).

The last major show of the year is coming up in a few weeks at the Whitman Expo in Baltimore. I anticipate having a better show there than I did in Long Beach.

Enjoyed, Chris.